Contemporary interpretations of slave narratives have kept the focus on the relentless cruelty of slave owners. Whipping and more whipping, repeated, horrific rape, humans reduced to beasts of burden and tools of their slave masters: it amounts to torture porn.

Male creators crafted Twelve Years a Slave, The Book of Negroes and Django Unchained – slave women’s stories are depicted in a way so violent as to make the viewer feel complicit in the abuse. Nothing can be learned from this.

Josiah, based on the life of Josiah Henson (born 1789, died in Dresden, Ontario in 1883)is no such tale. Charles Robertson, a Kingston scribe and author of the supernatural horror story Dark Church, has crafted a script told in dance and movement, a saga of literacy, redemption, hope and a kind of freedom.

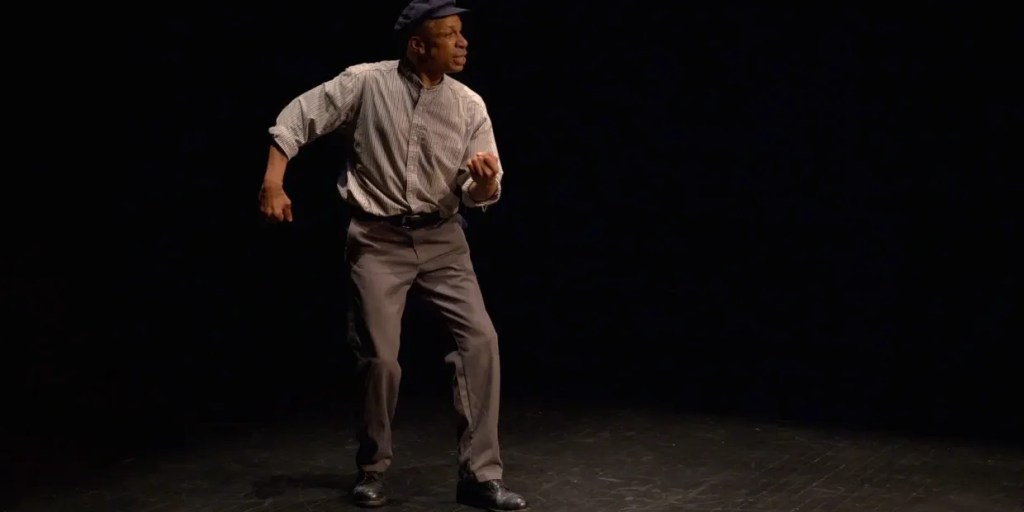

Tap-dancing phenom Cassel Miles, a triple threat who has been appearing in dance and musical shows since 1984, is Josiah. We meet the young slave as a boy, sold down the river with his mother by a Maryland slave owner. He’s considered too wilful, too prideful “for his own good.” He is, after all, a piece of property and must learn to accept that.

Josiah and his mother are sold to the highest bidder, Master Adam Robb, because he’s a “vigorous, healthy boy.” Robb is a brutal man “especially addicted to the vice of licentiousness.” He is “a beast who wants to be a man.”

Slavedriver and overseer Master Isaac Riley in the fields is even worse. His ultimate threat is to sell Josiah down the river if he doesn’t behave. This action is accompanied by an overhead sound of lashings – we are not exposed to any raw, open suppurating wounds on the back and shoulders here, thank goodness.

Long story short, Josiah learns to read, finds God, meets a preacher and becomes one himself, raises the $400 to buy his freedom and finally enters Canada crossing the border via the Underground Railway in 1830. There the play ends.

Charles Robertson is no Shakespeare; the text of this play is serviceable, but nary a word of poetry creeps in. And it is way too long. A one-man show is normally an uninterrupted work of 85 to 90 minutes. Neither performer nor audience member can concentrate on a work such as this for longer than 90 minutes. So Robertson chooses to break the play after an interminable first act for an intermission. Then, for another hour or so we learn of Josiah’s journey on the Underground Railroad. Thus, two plays, both of which have been done before, more movingly and profoundly in works such as Middle Passage (1990) by Charles R. Johnson and the fascinating, poetic Underground Railroad (2016) by Colson Whitehead.

The one-man show that my companion and I were keen to see is Josiah entering Canada in 1830. What happened to him after that?

As for Cassel Miles, he is a lovely mover, can sing and mime and keeps the cadence of the piece. But the speaking voice is not his tool. He does a reasonable job of impersonating all the characters, male and female, but the voice of Josiah is not distinct. Josiah should have something akin to a preacher’s or an orator’s voice, and it should change over the course of a long life seen from boyhood into middle age. It doesn’t.

Still, I’m glad I saw Josiah.

Josiah

Written by Charles Robertson, directed by Jim Garrard and performed by Cassel Miles

Produced by Thousand Miles of Bricks Productions

At the Alumnae Theatre, Toronto, until February 7

Photo, courtesy of the producers: Cassel Miles