We all could use some exuberance in these troubled and angst-ridden times. A good place to find it is at the Citadel Dance Exchange, a Montreal-Toronto collaboration, now in its second week at the Citadel on Parliament Street in Toronto.

A joint initiative with The National Ballet of Canada’s Creative Action program, the exchange of dancers and choreographers from both cities has resulted in a high-octane show sure to get feet stomping, hands clapping and spirits rising. Catch the final performance Saturday April 12, at 8 pm.

Hair in pigtails, garbed in a shiny suit a size too big for him, back to his audience, Montreal’s Sovann Rochon-Prom Tep makes an inauspicious start to “Soft manners,” taking slow, sideways and back and forth steps toward a microphone stage front, where he turns to face the audience, a little bashfully, and begins to undress.

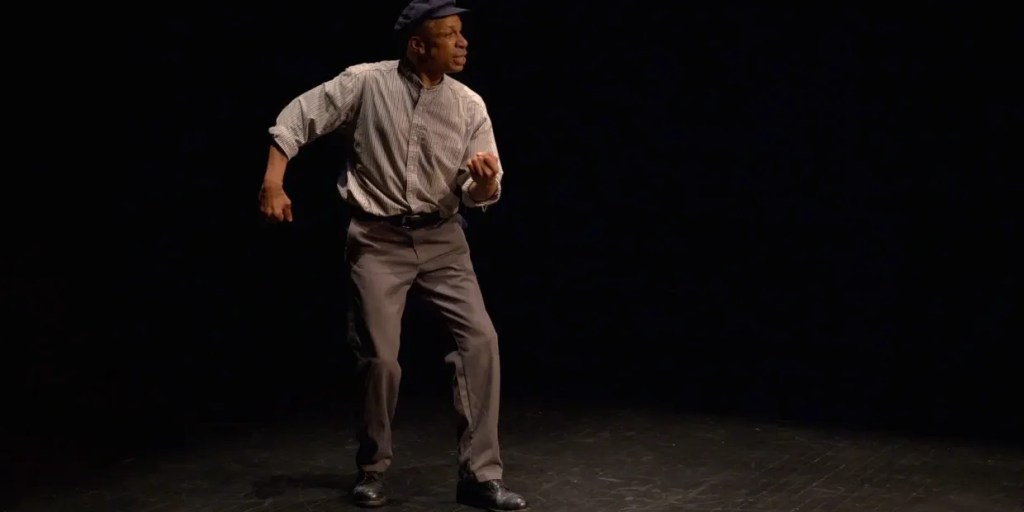

“Soft manners,” is an inward-looking solo that morphs through several costume changes, Tep peeling down to underpants at one point, to reveal a street performer of high caliber. This Montrealer whose breakdancing cred got him from the sidewalk to the stage, performing with Animals of Distinction and RUBBERBAND, knows how to engage an audience. During an interlude where he perches on a stool, microphone in hand, the dancer offers a little autobiography. Then, with escalating energy provided by a soundtrack of electronic beats and lounge-style music, he runs through a repertoire of moves from voguing to spinning on the floor, moving with style for the sheer joy of the dance.

Carol Anderson, a founding member of Toronto’s Dancemakers, a choreographer teacher and dance writer, set a memorable solo, “Elsinore/Soliloquies” on Julia Sasso in 1999. She has reworked the themes and images of the solo, expanding the dance into a work for four dancers, including Sasso, as sure-footed and emotionally expressive as ever. In this well rehearsed 18-minute piece, Toronto performers Sasso, Sully Malaeb Proulx, Katherine Semchuk and Natasha Poon Woo combine and recombine in muscular, gravity-defying duets, trios and a quartet, to the evocative classical-sounding strings of composer Kirk Elliott.

An accompanying poem and the sounds of waves washing on a pebbly shore or the crackling of a campfire, suggests that nothing is lost in dance. What was old can be reborn, reimagined on new bodies, captured fleetingly in timeless moving images.

In the 15-minute show closer, Toronto’s TUFF – The Unknown Floor Force – performs “Binary Codes.” Coming on strong and menacing in baggy pants and dark hoodies they brawl like a street gang. But, once stripped down to white undershirts, they turn collegial, but competitive, as a b-boy ensemble. Jayson Collantes, Mark Collantes, Keimar Russell-Farquarson and Bryce Taylor scrum like a rugby team, spin like tops and get the audience hooting and hollering to their beats like it was springtime on a basketball court.

Citadel Dance Exchange Week Two

Produced by Citadel + Compagnie in collaboration with the National Ballet of Canada Creative Action program

At the Ross Centre for Dance, Toronto, until Saturday, April 12, 2025

Photo of Natasha Poon Woo, Julia Sasso and Sully Malaeb Proulx by Drew Berry