In all the years of enjoying the National Ballet of Canada’s mixed program I have never seen a program so well attended and so loudly appreciated. You might, without too much exaggeration, call this artistic director Hope Muir’s perfect mix.

This two-hour program, with one last performance today, Sunday, March 2, opens with something old, Antony Tudor’s The Leaves are Fading, marking 50 years since its world premiere at the American Ballet Theatre in July 1975. The something new is an NBoC commission, Marco Goecke’s thrilling duet Morpheus’ Dream, set to Keith Jarrett’s Budapest Concert, Parts VII and VIII, and Lady Gaga’s rousing love/hate anthem, “Bad Romance.”

And for the finale, something reinvented: David Dawson’s brilliant re-conception of Antonio Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, to a score by Matt Richter that reshapes the original four violin concertos in a dramatic way.

The evening pays equal homage to a youthful, skilled edition 2024-2025 of the National Ballet and the talented players of the National Ballet Orchestra under the sensitive directin of principal conductor David Briskin.

The Leaves are Fading is a late work of Tudor’s (1908 to 1987) and the most unfussy, in its purity of form and abstract conception. Tudor set it to chamber music for strings by Antonín Dvořák, another perfect mix, as it turned out. For this dance is about a woman looking back on her life from a long distance, as the autumn leaves are falling, contemplating the years with a fusion of nostalgia and regret.

Alexandra MacDonald, in the role of the woman looking back, performs by turns wondering, nostalgic, solemn and celebratory. Leaves gives parts to nearly 20 dancers, all of them as light on their landings as the faded falling leaves. Tirion Law and Naoya Ebe performed a particulary poetic pas de deux near the end.

Tudor’s neo-classical signature is etched with precision on this work, the dance inseparable from Dvořák score, with the orchestra’s fulsome violin section performing as one, like the lyrical voice of the woman reflecting on life’s seasons.

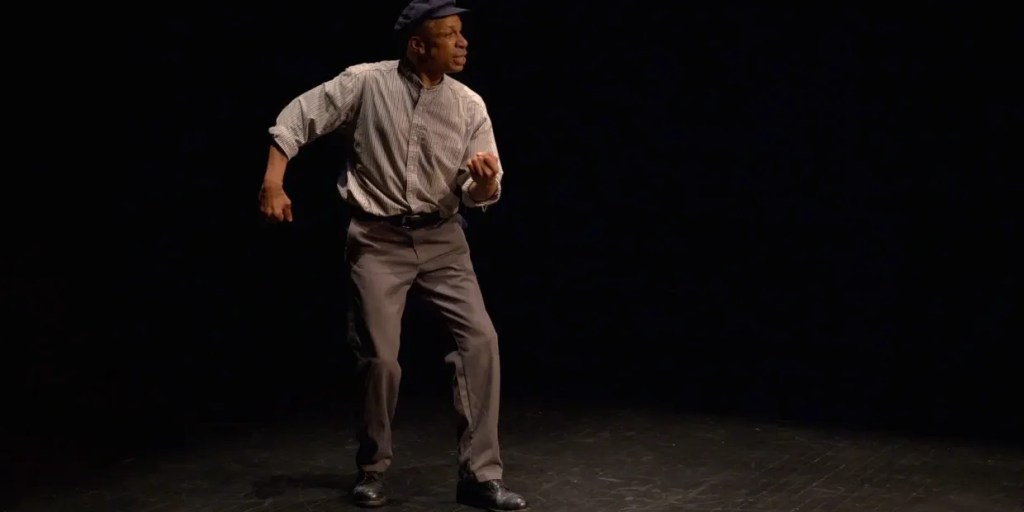

After the autumnal Tudor, Spencer Hack bursts onto the stage like a bolt of lightning in Morpheus’ Dream, named for the god of dreams. To call the 10-minute piece edgy is anunderstatement. German-born Goecke, once associate choreographer of Nederland Dans Theater, is a favourite of European ballet companies, lauded with good reason for works such as Nijinsky and The Big Crying.

In this commission, supported by the Gail Hutchison Fund, the choreographer seemed to find the bad-boy, bad-girl element in Tene Ward and Spencer Hack. Their muscular partnering makes for an exciting push-pull of love on the hoof and a not-so-playful lover’s quarrel, bringing the audience to its feet with a roar, completely invested in this dream of the dynamics of an affair to remember. Lady Gaga says it all in what many a woman might want as her theme song, the Jarrett determinist keyboard playing counterpoint to her ballad “Bad Romance:” I want your love and I want your revenge.”

British dancer/choreographer brings his striking, abstract, full-immersion Four Seasons to the NBoC stage for its North American premiere. Dawson was finely inspired in this stark, yet fully absorbing dance with the recording Recomposed by Max Richter: Vivaldi, The Four Seasons. Nothing is lost but much is gained in Richter’s streamlining of the main themes of the Vivaldi seasons to give it a bigger sound and more range for the dancers.

This reinterpretation of The Four Seasons does not supplant James’ Kudelka’s more literary reading of the Vivaldi classic; rather Dawson’s piece with its dramatic lighting and moving geometric shapes on stage to represent the rise and fall of the light, of the associations with the seasonal changes that have governed our lives for millenia.

Violin soloist Aaron Schwebel shows the way, as swarms of the Ballet’s nimble best criss-cross the stage in colour-coded leotards meant to represent the intermingling of the seasons’ themes.

The Four Seasons / Morpheus’ Dream / The Leaves are Fading

Performed by the National Ballet of Canada at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, Toronto February 26 to March 2, 2025

Photo: Calley Skalnick and Spencer Hack in The Four Seasons. Credit: Karolina Kuras