Once upon a time, David Danzon, the peripatetic artistic director of Corpus Dance Projects, decided to embrace Japanese theatrical traditions to come up with a cross-cultural contemporary fairy tale.

After touring shows through Japan, Corpus partnered up with Osaka’s 53-year-old Kio theatre company to co-produce Mukashi Mukashi, a contemporary interpretation of two characters central to European and Japanese folklore: the wolf and the crane, respectively.

The kid-friendly show, launched at a festival in Japan last October is playing now, for its first North American run, at the Theatre Centre in Toronto, until Sunday, September 29.

Mukashi Mukashi is a madcap mash-up of physical theatre from two distinctly different cultures. Corpus and Kio found their theatrical modus operandi quite compatible. Danzon worked with the Kio company to incorporate Kabuki, Noh, Bunraku (body puppetry) and Kyogen (the comic interludes between acts in a Noh play) into the Corpus brand of physical theatre. He layers these expressive movements, scene by scene, to create a melding of human and animal, as any good fairy tale would. The skills on display here revolve rapidly through mime, to dance, puppetry, mask, clown, live origami-making, Asian shadow puppetry, to a manic, sequin-jacketed TV game-show host — all accompanied by Anika Johnson’s evocative soundscape.

By turns hilarious and thought-provoking, Mukashi Mukashi proceeds through a series of nine short scenes, the performers speaking mainly Japanese, with a few lines of English thrown in. There is not a lot of dialogue, but English and French surtitles, white on black panels, spark memories of the talk panels in the silent films of Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, early influences on Danzon’s comedic practice. The dream-like sequence follows an arc from mortal danger through comical transformations, to peace and fulfilment, tapping deep into the collective unconscious.

In The Uses of Enchantment (1976) child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim famously argued that the violence and fantastical nature of traditional fairy tales were not to be shunned in favour of anodyne realist children’s literature, because stories such as Little Red Riding Hood cathartically deal with primal fears and lead to healthy childhood psychological development. Mukashi Mukashi is enchantment at its best.

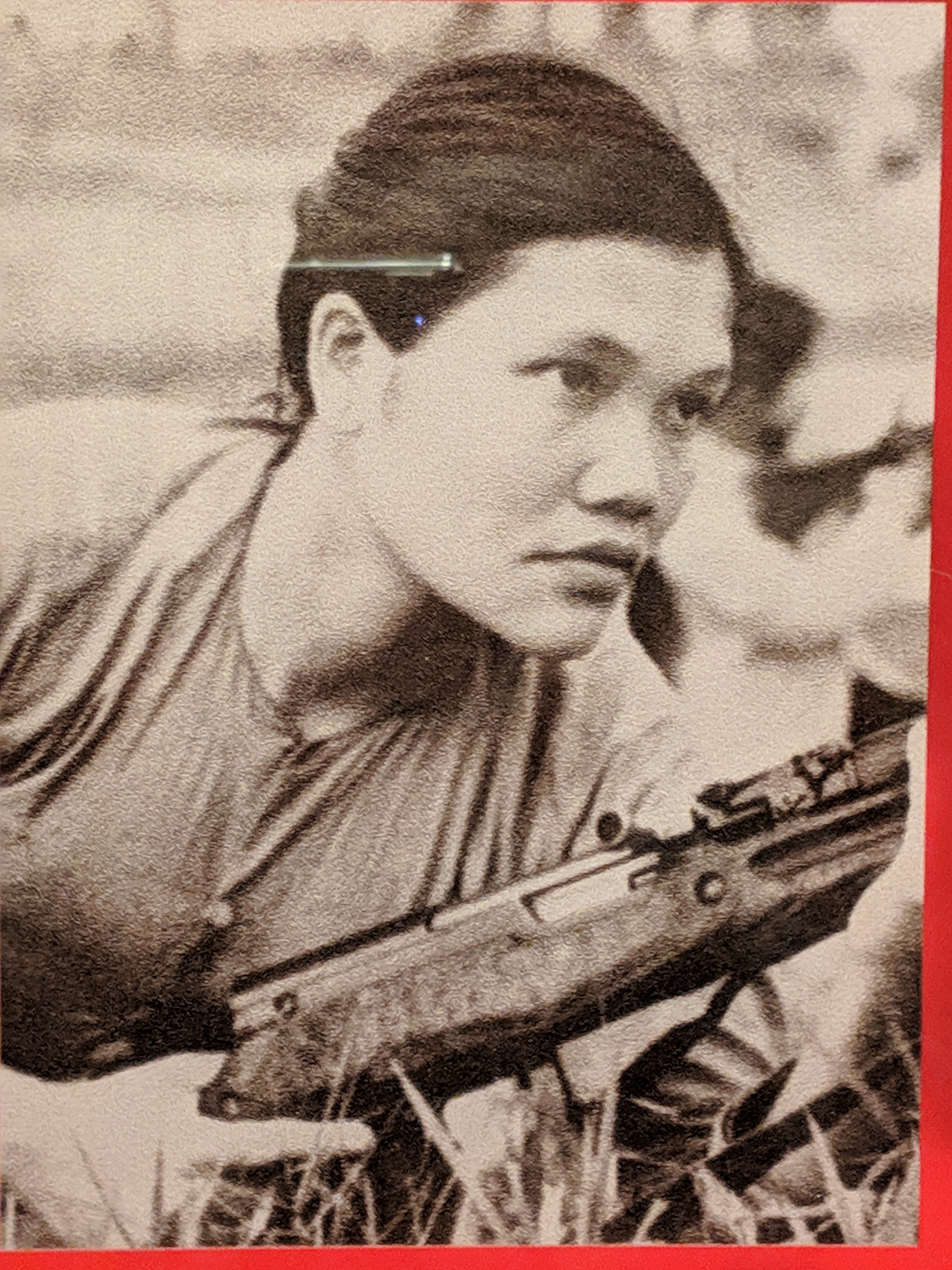

Guffaws greet the opening scene, as performers Sakura Korin, Kio artistic director Kohey Nakadachi, Takako Segawa and Kaitlin Torrance arrive on stage, costumed by designer Atsuko Kiyokawa, in black tights with big bushy wolf tails. They are soon howling at the moon overhead and with the next scene we’re plunged into the fantastic, as Nakadachi in a wolf headpiece morphs from the big bad wolf to little red riding hood being tantalized by Mr. Wolf, to later hilarious scenes when he’s begging for sympathy from little red riding-hood. Mr. Wolf’s funeral ushers in scenes involving the performers making origami paper cranes – in one case screwing up, prompting a live demonstration of how to make a paper crane.

The crane is a powerful symbol in Japanese culture. Considered mystical creatures who may have lived for eons, they are thought to bring luck and prosperity, peace and hope. A paper crane may be gifted as an emblem of honour. The wings of the crane took mortals to paradise, hence the scenes with Kaitlin Torrance as an ethereal crane, arms gracefully spread, her signature origami crane or orizuru atop her head. The final scenes bring a soothing feeling of something transcendent after the set-tos of big bad wolf, grandma and little red riding hood.

A note to parents: make sure your child is familiar with the story of the Little Red Riding Hood and maybe take them around the exhibition created by Carolin Lindner displaying Japanese masks and explaining the four traditions of Japanese theatre and the making of orizurus.

Photos: The Big Bad Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf takes on an outsized little red riding hood and Kohey Nakadachi as Mr. Wolf.