COC Free Concert Series-2011-1-28

An important project, Solo Dance Xchange brings together 22 performers — on screen and live – from a broad spectrum of dance disciplines.

Introduced by producers Karen and Allen Kaeja, the show combines a film in which each of the dancers improvises a dance in the location of his/her choice and a staged segment when the dancers do two-to-three-minute solos accompanied by live music from Eric Cadesky, Laurel MacDonald and Phil Strong.

The outcome? Some predictably fine performances, some merely predictable and a few quite surprising delights.

Allen Kaeja’s 30-minute film, XTOD: Moments in Reel Time, is a nicely edited panoply of 22 dancers doing minute-long improvised solos in locations of their own choosing. Using only natural light, DOP Hernan Morris captures some lovely movement, but the footage lacks the finesse of a studio dance film. By virtue of the subject matter, the HD video reels feels improvised.

Many performers chose water settings, and even long-time Toronto residents will be surprised by the natural beauty found within the confines of Hogtown. Some are romanticized: Jasmyn Fyffe walks a watery concrete pier in a flowing robe; Claudia Moore goes pagan atop the giant rock in Yorkville; Karen Kaeja gyrates on the foredeck of a yacht, the CN Tower looming over her shoulder.

Some, such as Nova Bhattacharya posing on the rim of the fountain pond amid bank towers, opt for high contrast; Delicate-boned Hari Krishnan goes gangsta under an expressway. Two indigenous performers partner with nature, Brian Solomon enraptured in the branches of an old maple tree, Santee Smith, in a long blue gown, dipping into the waters below the Scarborough bluffs. Allen Kaeja charges into a wild tumble off a bicycle down a grassy ravine slope.

As the lights go down on the Streetcar Crowsnest stage, a few dancers, who will sometimes double as stage hands, sit in a row of chairs facing the audience, the trio of musicians set up stage right.

Solo Dance Xchange is in no way a competition, but mastery will out, and can’t help but draw an audience closer to the stage and inside the dancer’s moves, if only we could. The magnificent Peggy Baker in sleek jeans and grey t-shirt grasps a stick like a baton across her upper chest. In a few exquisite minutes, she strikes out with it like a warrior, uses it as a pivot point for a series of graceful floor manoeuvres, crawls hand over hand, then rises up free and strong with her mast held high.

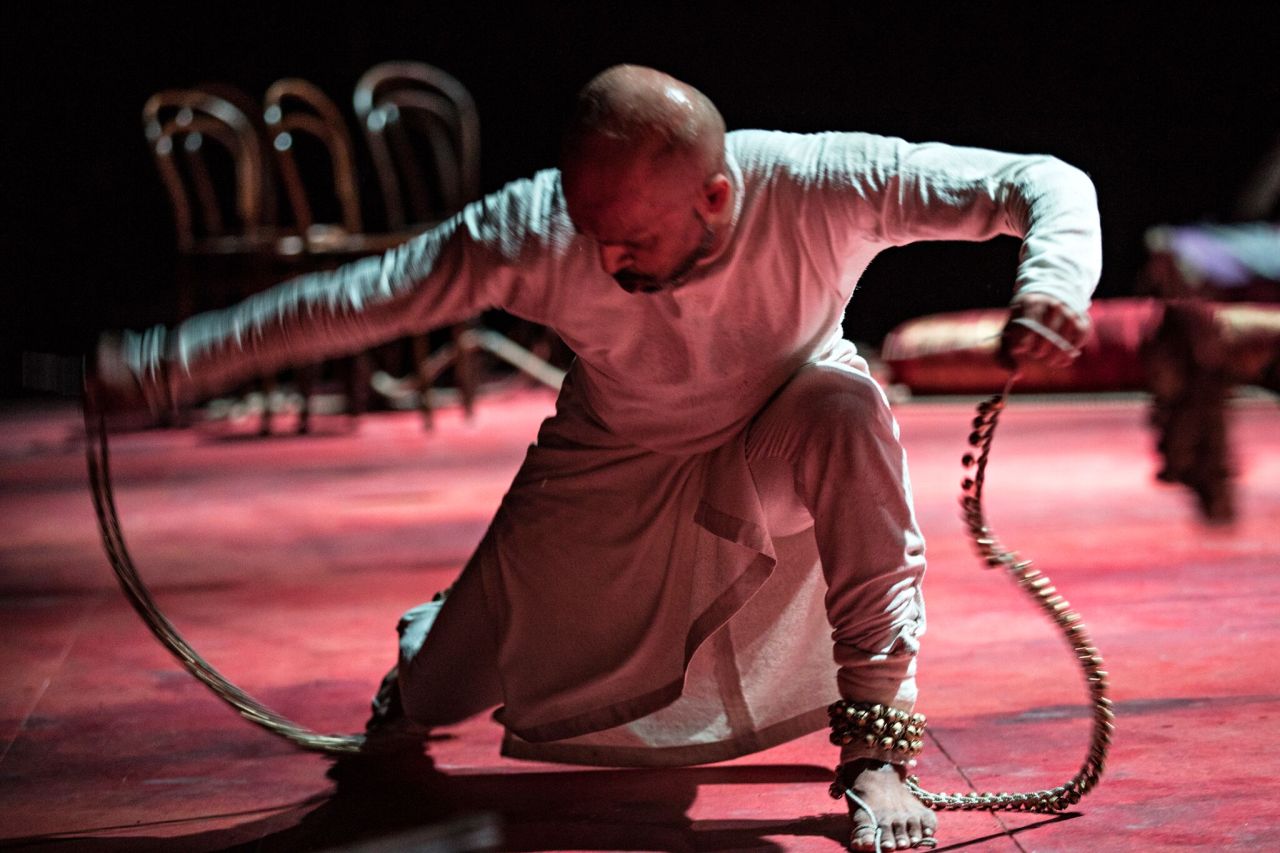

Robert Desrosiers is electric: arms spread or held tight; tiny rapid steps accelerating to the beat of drums, sculpting the air with measured, vocalizing from whispered breaths to almost silent howl. And Robert Stephen, bare-chested in blue tights, executes a breathtaking pas d’un that is all about virtuosity without showing off.

Others in this category are Bhattacharya, androgynous and fascinating in a barely Bharatanatyam, modern dance progression and William Yong in long black straight hair, holding a daisy, simpering from farce to dignified, balletic beauty. Shawn Byfield taps like a genius in white pants, adding his own rhythms to the tradition of black tap dancers.

Unexpected delights of Solo Dance Xchange include: Esmeralda Enrique, girlish in a short black dress and shocking red flamenco shoes, clacking her castanets along a diagonal path of light; Ben Kamino, in nothing more than his tattoos, comically hefting a heavy folded table like frail, trembling muscleman in need of more strength; and Emily Law, who partnered with her costume, a full-length, diaphanous, kimono-like gown, its sleeves fluttering banners in her stately procession toward and away from us. Also, versatile Michael Caldwell in an Asian pointed straw hat, face obscured to the percussion of gongs and bells, moving with control toward a deliberate crumbling of his own spectacle.

So go see Solo Dance Xchange – tonight’s the last – no matter what you fancy in the way of dance. You can’t be disappointed.

Solo Dance Xchange

Dancers: Mi Young Kim, Roula Said, Robert Desrosiers, Santee Smith, Michael Caldwell, Roshanak Jaberi, Esmeralda Enrique, Nova Bhattacharya, Allen Kaeja, Ofilio Sinbadinho, Jasmyn Fyffe, Pulga Muchochoma, Benjamin Kamino, Emily Law, Karen Kaeja, Shawn Byfield, Peggy Baker, William Yong, Claudia Moore, Robert Stephen, Brian Solomon

Soundscore: SDXtet Eric Cadesky, Laurel MacDonald, Phil Strong

At Streetcar Crowsnest, Toronto, Feb 1 through 3 at 8 pm

Photo of William Yong by Aleksandar Antonijevic; Peggy Baker by Chris Hutcheson; Pulga Muchochoma by Allen Kaeja