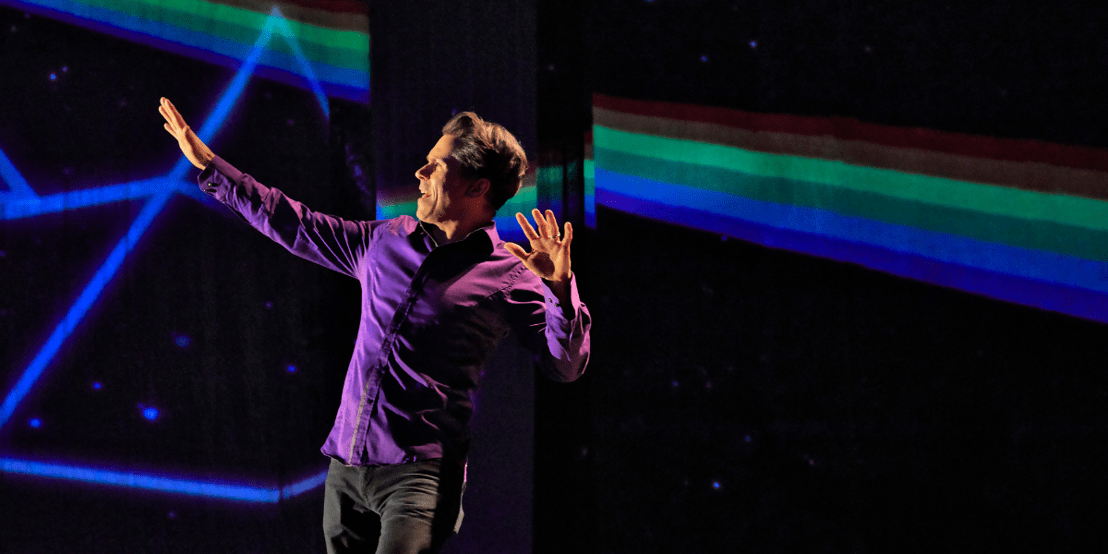

At the Venice Biennale this summer visitors lingered long at the Canadian pavilion, captivated by One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, as it played on three big screens, subtitled in Italian, French and English. A production of the Baffin Island Isuma collective, One Day is directed by Zacharias Kunuk and compellingly presents a story, in Inuktitut, of a day in 1961 when Noah (Apayata Kotierk) and his clan, out on the ice to hunt and trade, spy an approaching dog team and sled. This turns out to be a white man named Boss (Kim Bodnia), a Canadian government official who has come to tell Noah and his companions that they must prepare to leave their way of life and join a community where their children will go to school. Adding to the poignancy and authenticity of the film is the understood notion that the Inuit culture faces a still greater peril in the form of climate change and the melting of the polar sea ice.

Tonight, the film screens at Toronto’s Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema Hot Docs at the opening of the 20th edition of the imagineNATIVE Film & Media Arts Festival, 18 years after the opening night screening of Kunuk’s ground-breaking Atanarjuat The Fast Runner. imagineNATIVE, the largest indigenous festival of its kind in the world, serves as a platform, for first nations’ film and media and encompasses a professional development component, the imagineNATIVE Institute, as well as an awards program.

From tonight through Sunday, October 27, imagineNATIVE will present 126 film and video works in 30 languages from 18 countries and 101 indigenous nations, including nine features, 13 documentary features, and 12 short film programs. Watch for The Incredible 25th Year of Mitzi Bearclaw, a touching feature directed by Shelly Niro, starring MorningStar Angeline and featuring the amazing Billy Merasty as Mitzi’s father.

The outstanding filmmaker Alanis Obamsawin returns to the festival with an NFB production, Jordan River Anderson, the Messenger. This documentary tells the story of a Cree child born with overwhelming challenges and how a dispute over his care led to major changes in access to healthcare for indigenous peoples in Canada.

Among many short films of note, the 2001 Gwishalaayt – The Spirit Wraps Around You celebrates the life and work of ‘Namgis filmmaker Barb Cranmer, who died earlier this year. She was from the important Kwakwaka’wakw family in Alert Bay, British Columbia that did so much for the continuance and preservation of their art and culture.

Wik vs Queensland is a 2018 feature documentary from Australia directed by Dean Gibson relates how the aboriginal people of Wik take on the Queensland government and land developers to ensure rights to their traditional lands.

Among special events in the festival is a Friday presentation at the Art Gallery of Ontario of Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus [infected], a multi-channel projection and immersive experience followed by a conversation with curator Julie Nagam. And on Thursday, the popular imagineNATIVE Art Crawl takes in five galleries with visual art works, curatorial and artist talks and a live performance, starting at Onsite Gallery and ending at the Toronto Media Arts Centre.

imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival

October 22-27, 2019 at Toronto locations

For more information call 416.585.2333 or visit www.imagineNATIVE.org

Photo: Still from One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk