Indigenous Dance Double Bill

Indigenous Dance Double Bill

Luu hlotitxw: Spirit Transforming by Dancers Damelahamid

NGS (Native Girl Syndrome) by Lara Kramer

Native Earth Performing Arts and DanceWorks CoWorks

Aki Studio, Daniels Spectrum, Toronto

April 21 to 23, 2016

Native Earth Performing Arts presents two indigenous dances that are poles apart, both geographically and culturally.

Luu hlotitxw: Spirit Transforming is based on traditional Pacific northwest Gitxsan dancing, singing and storytelling about a young man’s self-realization as he meets life’s challenges. NGS (Native Girl Syndrome) is purely contemporary in form, based on the degrading urban experience of the choreographer’s grandmother; it is a journey into alienation and self-destruction. Both need to be seen.

In Luu hlotitxw, Rebecca Baker, choreographer Margaret Grenier and Jeanette Kotowich enter the stage in long fringed dresses, button blankets emblazoned with totems, beaded headbands, moccasins, leg wrappers and decorated dorsal fins sticking out of their backs. These are the spirits of the orca and they move in ways to suggest the playful rising and diving of the Pacific killer whales – seen life-size in a video projected on the back screen. They chant as they move with silent footfalls in circular patterns.

Nigel Grenier sings too, in melodic phrases repeated with slight alterations (“yay ha hay /yo ha ho”). On first entry he bears a large bear mask in front of his face. The women surround him as he returns, bare-chested, to kneel on stage. They place cedar fronds in front of him. These are understood to be healing or protective.

The young man paints a black X on his chest with a paste given him by one of the women. He wears a second mask on re-entry, like the face of a small hunted animal. It is marvellous to see how these masks are animated by the dancer’s movement, so we sense without being told what this story is all about. Another figure, a warrior with a very elaborate mask, comes in. The warrior attaches little heads to his mask, making him more animal-like and fierce, while the young man removes pieces of his mask to reveal the human beneath. In a clever bit of staging, we see him as a silouette on the screen depicting a forest, taking his rightful place in the universe.

In Montreal choreographer Lara Kramer’s dance for Angie Cheng and Karina Iraola, NGS, the women of the street, drugged, drunk or beaten down, are made faceless, their hair or their headwear obscuring their identities. This is a powerful reminder of the missing or murdered aboriginal women of Canada: unknown and unsought. The ubiquitous duct tape is a symbol of how they piece together a precarious existence.

Dressed like hookers in assorted found and damaged items, they stagger about, Iraola pushing a stroller and Cheng leaning over an old pram with a native symbol painted on it. At the back of the stage, a huge plastic tarp hangs in the rough shape of a teepee. Iraola makes her way to music that goes from a loud, scratchy din to rock songs, such as “These Eyes,” to heavy metal music and drumming to something with the ironic lyric “…walk easy, walk slow.” In a head-hanging stupor, Iraola dresses in fake fur and huddles under her makeshift tent. Cheng, bare-breasted for part of her perambulations, rolls out a Canadian flag with a native image over the maple leaf. From one of her bags, she pulls out plastic miniatures of people and animals and places them in neat rows on the flag, as if this would make a home.

NGS takes a stereotype, magnifies it and flings it in our faces. The long silence at the end, as the two performers lay hunched over in the dark, is particularly affecting.

Top: Angie Cheng & Karina Iraola Photo by Marc J Chalifoux

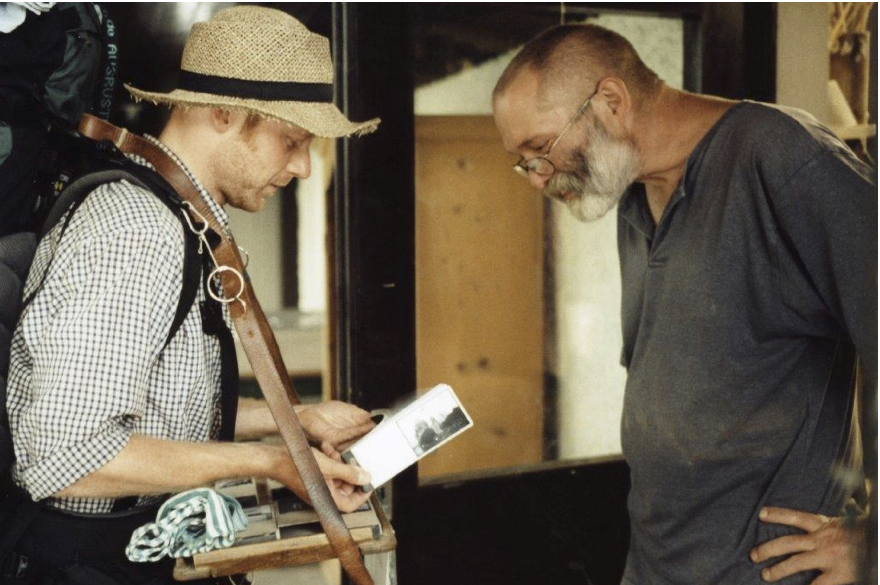

Below: Dancers Damelahamid Photo by Derek Dix